World View

Sometimes people speak of Colorado as if it suddenly sprang into existence in the mid nineteenth century. However, people have been living here for over ten thousand years. North America, often called Turtle Island by many of the original inhabitants, has been radically altered. 43,000 Square miles are covered by impervious surfaces (roads and rooftops.) 40 million acres are covered by turfgrass. Doug Tallamy, author of Bringing Nature Home, says that 98 percent of the lower 48 states has been altered for human use.

Driving across the prairie it can sometimes be hard to find wildflowers amidst the croplands and introduced grass species. Occasionally we find areas that are relatively undisturbed, or left alone long enough to begin to recover. These are windows into Turtle Island. Indian Reservations are such places, both in terms of people and plants, where we can touch the original land and see the world through the lens of the original inhabitants. In 1977, I set out to discover these places and people. I lived with a Lakota Medicine Man and his family for the summer and developed deep and lasting relationships with the people. I am part of their family and they are part of mine.

Little is really known about indigenous uses of plants (although much has been written.) If a native person shows you a medicinal plant he or she may well admonish, “Don’t tell anyone.” It’s not that they are greedy or selfish, in fact quite the opposite; in native cultures people will often endure hunger and thirst, and shed their life’s blood for the benefit of the others. The protection of this information is rather because native people know how our materialistic culture works, that everything is for sale, and everything is subject to exploitation.

The relationship to plants in Native-American culture is very different than Euro-American culture. When a traditional person is looking for a plant they may sit down by the first one they find and offer tobacco. They might pray or talk to the plant. Then one begins to notice that these little plants are all around. Relating to plants this way is a matter of acknowledgement and respect that comes from a perspective of humility, gratitude, and relationship – the foundation of healing in traditional native culture.

Not acknowledging plants as relatives reduces them to “things” to be used rather than beings that contain their own wisdom and power. For this reason, simply having the ability to identify plants is not enough. In native cultures it’s not the plants alone that can heal people but the qualities of the person administering them and the sacred context of ceremony.

Due to the awareness of the predominant culture’s propensity for exploitation native people have been protective of this knowledge. Therefore many scholars have traveled to Indian reservations and concluded that the knowledge and uses of plants have been lost. However, the knowledge is there, like Turtle Island, waiting to be discovered by those who can see, as the Lakota say, with the Cante Ista, “the eyes of the heart.”

The knowledge of plant uses among Native Americans came from experimentation and insight and has been transmitted from person to person in a long oral history. Euro-Americans have benefited from the knowledge of plants accumulated by Native Americans as in the case of Joe Pye, an Indian who used the plant named after him (Joe Pye Weed) to cure a typhoid outbreak, in colonial Massachusetts.

John Neihardt’s hauntingly poetic Black Elk Speaks, about the life of an Oglala Holy Man, provides an example of the knowledge of plants through spiritual insight. In a vision, Black Elk saw a particular plant being used to cure illness. Later he and his friend, One Side, sit on a hill, watching hawks circle a spot nearby and he says, “I believe that yonder grows the plant from my vision.” They ride over to the spot and, “There right on the side of the bank the herb was growing, and I knew it, although I had never seen one like it before except in my vision.”

The People

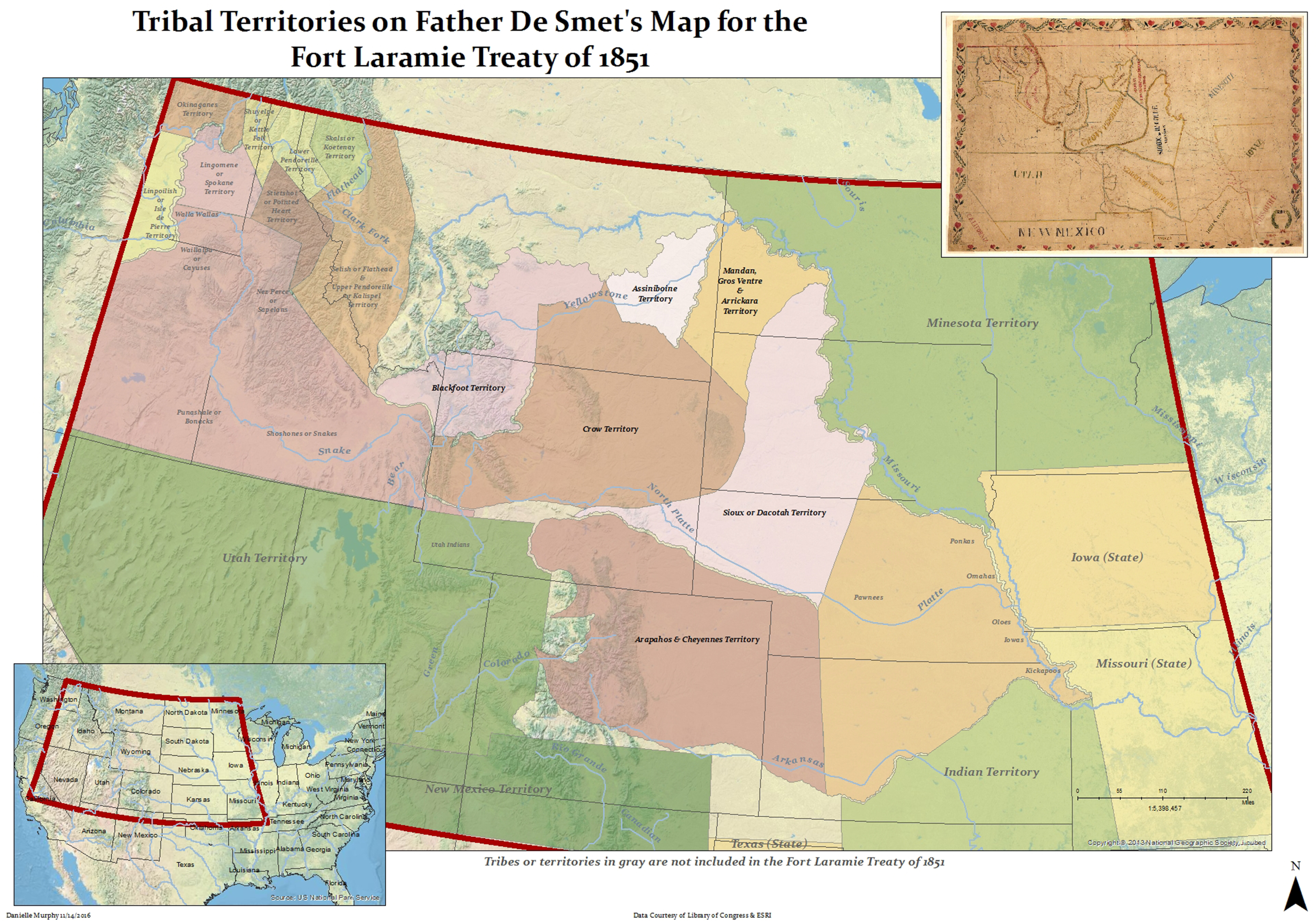

The territories of Indian Tribes were constantly shifting and most native people in the State were migratory. The Utes are thought to have been in the region as far back as 10,000 years ago. There was a thriving Pueblo culture in the southwest corner of the State which began to die out around 1000 A.D. when the climate became too dry for farming. The Arapaho and Cheyenne moved up and down the front range in what is now Colorado and Wyoming. The Pawnee ranged from Eastern Colorado into Nebraska and Kansas. Northeastern Colorado was included in the territory of the Lakota when the Fort Laramie Treaty was signed, in 1851.

The 2010 Census Bureau shows there are 104,464 people who identify as American Indian alone or in combination with other races living in Colorado. With Denver’s central location between the desert tribes of the Southwest and the plains tribes east of the Rocky Mountains, the metropolitan area has become a hub for Indian Country. These descendants of the Cheyenne, Lakota, Kiowa, Navaho, and at least 200 tribal nations are an integral part of the City’s social and economic life. Despite their diversity, they are a tight-knit group, sharing the same strong commitment to family and cultural survival.

The Plants

I use the Lakota names because of my personal connection with the people and because the Lakota uses of plants have been well documented. Between 1902 and 1954 Father Eugene Buechel, a Jesuit living with the Sicangu Lakota on the Rosebud Reservation in South Dakota, collected over 24,000 words including the names of plants and their uses. These were published in the first Lakota-English dictionary. Other writings include Lame Deer Seekers of Visions by John Fire Lame Deer and Richard Erdoes, published in 1972.

In the Lakota language plants are named for where they are found, how they are used, or for their distinguishing characteristics.

Artemisia ludoviciana (Prairie Sage) is called pȟeží hóta, “something gray in the grass.” This plant is used for purification. Artemisia tridentata (Big Sagebrush) is pȟeží ȟóta tȟáŋka, which means the same as above but bigger.

Asclepias pumila (Low Milkweed) is čhešlóšlo pȟežúta, which means diarrhea medicine.

Galium boreale (Northern Bedstraw), čhaŋȟlóǧaŋ ská waštémna, is traditionally worn under the belts of Lakota women as a sashay. The name means “good white herb” because of its wholesome hay-scented fragrance and white flowers.

Before drugstores and super markets people had to find food, medicine, and everything they needed, in nature. Doing that required a tremendous amount of knowledge about plants and animals, the various ecological zones, where things grew, and phenology; the study of periodic plant and animal life cycle events and how these are influenced by seasonal and inter-annual variations in climate, as well as habitat factors (such as elevation). Timing is critically important when harvesting plants for food and medicine. Plants such as milkweed can be beneficial at some times and may be toxic at others.

tremendous amount of knowledge about plants and animals, the various ecological zones, where things grew, and phenology; the study of periodic plant and animal life cycle events and how these are influenced by seasonal and inter-annual variations in climate, as well as habitat factors (such as elevation). Timing is critically important when harvesting plants for food and medicine. Plants such as milkweed can be beneficial at some times and may be toxic at others.

There are also ceremonial reasons connected with harvesting plants. Green Ash, Fraxinus pennsylvanica, pse ȟ tíŋ čháŋ, are used for pipe stems because of their pithy core that can be burned out easily. It is said that trees are protected by the Thunder Beings (Wakinyan Oyate) and ash stems can only be cut in winter, before thunder. Stems cut in springtime, after thunder returns, will crack.

Some particularly valuable and efficacious plants were (and are) gathered, dried, and stored. Others are simply gathered and utilized as needed and as available. People traveling through different types of terrain could find plants for various common ailments, as well as food, wherever they went and in any season.

Many native plants that may be growing in our gardens have traditional uses. Liatris punctata has been used to help stimulate appetite. Its Lakota name, tatéte čhaŋnúŋǧa, means that it faces the four directions. Echinacea (particularly E. angustifolia) is used for toothaches. Its Lakota name, uŋglákčapi, indicates the dried flowers are something you can “comb your hair with.” The name for common sunflowers, wacha zizi, means a “very yellow flower.” These were boiled to make an oil to soften the skin.

Where to see Indigenous Gardens in Colorado

For many years the High Plains Environmental Center (HPEC) in Loveland has held a mini powwow for third grade classes in the Thompson School District. This living unit on native American studies has connected students with Native Americans (The Iron Family of Fort Collins) for a direct transmission of culture, music, dance, and environmental stewardship. The event led to the creation of the “Medicine Wheel Garden” that functions both as a dance grounds and outdoor gathering space, as well as an ethnobotanical exhibit showcasing plants used by tribes of the High Plains, labeled with Latin, common, and Lakota names.

For many years the High Plains Environmental Center (HPEC) in Loveland has held a mini powwow for third grade classes in the Thompson School District. This living unit on native American studies has connected students with Native Americans (The Iron Family of Fort Collins) for a direct transmission of culture, music, dance, and environmental stewardship. The event led to the creation of the “Medicine Wheel Garden” that functions both as a dance grounds and outdoor gathering space, as well as an ethnobotanical exhibit showcasing plants used by tribes of the High Plains, labeled with Latin, common, and Lakota names.

The garden at the Ute Museum in Montrose, CO spans approximately a ¼ acre, and was originally installed in the 1990s when native plants were hard to find. It has recently been renovated using plants grown at Chelsea Nursery and HPEC. The renovated garden is still “in its infancy” according to restoration group member, Mary Menz.

Members of the Ute tribe have been involved with the garden and a group of elders participate on an advisory committee helping to create interpretive signs and document plant uses. Ethnobotanist Kelly Kindscher is also helping provide information about traditional plant uses. A Ute Museum goal is to be a place where native youth learn about traditional uses of plants. It’s also a place where Ute people come to collect edible cattails and other plants.

There is also a Ute garden at the nearby CSU Extension Office within the Mesa County Fairgrounds. It represents the lower elevations, while the Montrose site represents the middle elevations.

The Sacred Earth Garden, at Denver Botanic Gardens, York St, has a distinctly Four Corners feel to it. It features plants used for food, medicine, building materials, dyes, and ceremony by over 20 Native American Tribes from the Colorado Plateau (which includes parts of CO, AZ, NM, and UT.) It also includes a dryland agriculture garden incorporating Native American heirloom crops and traditional cultivation methods. When the garden was redesigned in 2000-01 there was an official blessing by native elders.

Understanding the relationship that Colorado’s indigenous people have with our native plants can help us to appreciate the original inhabitants of our State and inspire us to be good stewards of the lands that they hold sacred.