Welcome to a Public Affair here on KGNU. I’m Stacey Johnson.

As wildlife and plant habitat continues to decrease around the world and as many communities in the Western United States grapple with water supply shortages and strongly consider putting a halt to water-thirsty landscaping, questions mount if the existing ecological environment can sustain or flourish amongst an ever-growing built environment. In February, I sat down with Jim Tolstrup, executive director of the High Plains Environmental Center in Loveland Co. The 76-acre center includes gardens and trails, is surrounded by two lakes, and is open daily during daylight hours. What is unique about the High Plains Environmental Center is that this founder is a developer, and the center is located in the heart of the Centerra housing development. Because of its location within an urban neighborhood, the work of the High Plains Environmental Center focuses on a range of conservation issues. Chiefly among them is educating the public on land restoration, native plants, biodiversity, and sustainable landscapes in the built environment. Our discussion with Jim Tolstrup includes those topics and much more, including wetlands restoration, weeds, and turning a lawn into a native landscape.

What is the High Plains Environmental Center about, and what is its mission?

Our mission is to help communities incorporate nature as part of community design. We’ve worked with many developers and HOAs to create nature in the communities where people live. I say create nature cause these are not places that are typical conservation where we’re just drawing a circle around it and saying, “don’t build here, this is pristine natural area,” but more taking what was weedy-disturbed-farmland and turning it into natural areas, restored with native plants that can create habitat for plants and animals.

Can you briefly overview your professional background and how your journey brought you to the High Plains Environmental Center?

I studied horticulture at the Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University and had a garden design business in Kennebunk, Maine. Among my clients were first lady Barbara Bush and senior president George Bush and I really came into this from a perspective of ornamental horticulture although I’ve always loved wildflowers in nature, turtles, and frogs, even when I was a kid. So, the wildlife and wildflower part of it has always been part of things that I love. I was an estate gardener in Austin, TX, in the 90s and moved to Northern Colorado with my wife in 1998 and did landscape design for about four years. Then I was the land steward for a while, it was called the Shambhala Mountain Center, now called the Drala Mountain Center, and that’s where the notion of creating landscaping with native plants and the restoration and landscape design became one and the same thing. The reason was it’s at 8000 feet in elevation here in Colorado. There’s a pretty limited plant palette in terms of what we typically think of as ornamental plants, and it just made sense in that environment to focus on western native plants and Colorado plants, and that, for me, is where landscape design and ecological restoration really became the same thing. Then leaving there, I came here in 2007 and had the vision from the beginning of creating something like a Botanic Garden completely driven by the idea of utilizing native plants.

So, can you provide a brief history of the High Plains Environmental Center and your emphasis on native plants?

The High Plains Environmental Center is an interesting evolution because it began when Chad and Troy McWhinney brought their plans for Centerra, a 3000-acre, mixed-use, master-planned community, to the city of Loveland in the late 90s. The city said at build-out that this must remain 20% open space, so they hired a company called Cedar Creek to do a habitat evaluation of the land within Centerra. They particularly looked at the lakes, Houts Reservoir and Equalizer Lake, and recommended setbacks from the lake of anything from 75 feet to 300 feet. At that time, McWhinney was working with another company to build the residential part of the development of High Plains village; that company was McStain Neighborhoods. Their president Tom Hoyte was a lifelong conservationist and developer, which seems like two very different things, but he always said that where the bulldozers are out pushing dirt around, that’s where we have an opportunity to do some restoration and some conservation. He recommended creating this standalone nonprofit, donating the land identified by Cedar Creek to the nonprofit, and then creating a funding mechanism connected with a fee assessed along with the issue of building permits in Centerra to help pay for the management of that natural preserve in perpetuity. So, that was the beginning of the High Plains Environmental Center and its unique funding model and way of restoring nature in the midst of development.

Do you see that history or the potential of that being replicated elsewhere with other beginning developments?

Exactly yeah, that is very much what we are focused on. It was never our intention to corner the market on restoration but to make this something that all communities can do, and we actually help a lot of communities up and down the Front Range to either create this natural component at the very beginning and add that in the community design or to retrofit areas that are turf grass. HOAs come to us and say we’re spending $35,000 a year just taking care of this grass, is there some other alternative? We have helped lots of people to transform into restorative grass.

Just to confirm, can sustainable and native landscaping occur within a built environment or amongst urban growth.

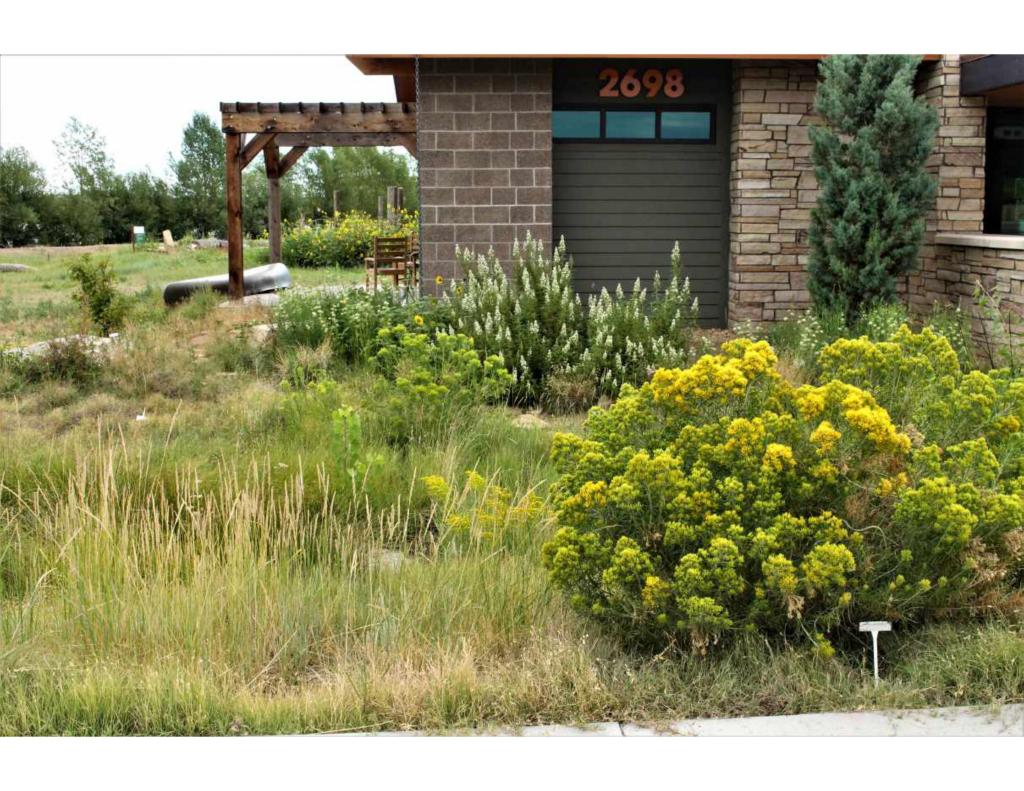

That is emphatically a yes, and I think it’s interesting that we have brought plans from the east coast, Europe, or other environments but a concept of what the world should look like. I think it goes back to a lot of people of European heritage and this notion of like the saying goes, “where sheep may safely graze” from England, the idea of these expansive parklands and lawns and so on. It just doesn’t apply to Colorado, but Colorado is beautiful, to begin with, so we worked so hard to make it turn into a New Jersey or East Coast environment, but we have beautiful plants that have evolved here and are adapted to this environment so yes absolutely here at the Environmental Center, we have extensive gardens that showplace the native plants throughout Centerra we’ve used a tremendous number of native plants in the landscaping.

Can you explain your native plant program?

For years I’ve been giving talks about how we need to create sustainable landscapes that our native pollinators and birds, etc., have coevolved with, and it’s critical that we use them in our landscaping, and it just makes sense because we’re preserving some Colorado’s natural beauty. Then people say, where can we get the plants and that’s a big question, it is it’s difficult to find truly native plants, and as a response to that, we have a nursery here at the High Plains Environmental Center where we’re growing over 150 species of western native plants from seed, and we make those available to the public, but it’s definitely mission driven because it is critical that we begin to change the landscape industry to using things that are what wildlife depends on and also plants that are adapted to this landscape.

I’m noticing the term Suburbitat amongst the High Plains Environmental Center vernacular. Can you define that for listeners and how it fits into the fold of your work and the work of the High Plains Environmental Center?

That term was created by the first executive director of High Plains Environmental Center, Ripley Hines, and combined suburb and habitat. The word itself is a response to the urban, suburban sprawl that started happening, you know, in post-World War Two populations growing and people wanting to have a picket fence and a house of their own and so on, and the problem with that is it’s just displaced so much of the habitat or taking farmland and turned it into sprawling homes and yards. And Doug Thalami, a person who wrote a book called Bringing Nature and Natures Hope, talked about we have 40 million acres of turf grass in the United States; we use more herbicides and pesticides per square foot on turf than any other single crop here in Colorado. We use 18 gallons of water per square foot per growing season for turfgrass, and nationally we use 800 million gallons of gasoline just to mow lawns, so there’s an enormous amount of resources being directed to this one crop that really doesn’t provide much of anything that supports biodiversity.

If you are just tuning in, this is a public affair in KGNU. I’m Stacey Johnson. On today’s segment, we are visiting with Jim Tolstrup, executive director of the High Plains Environmental Center, discussing a range of conservation topics within an urban environment.

Can you describe what a sustainable native landscape looks like, and would that be similar to what the Front Range region looked like prior to non-natives settling here?

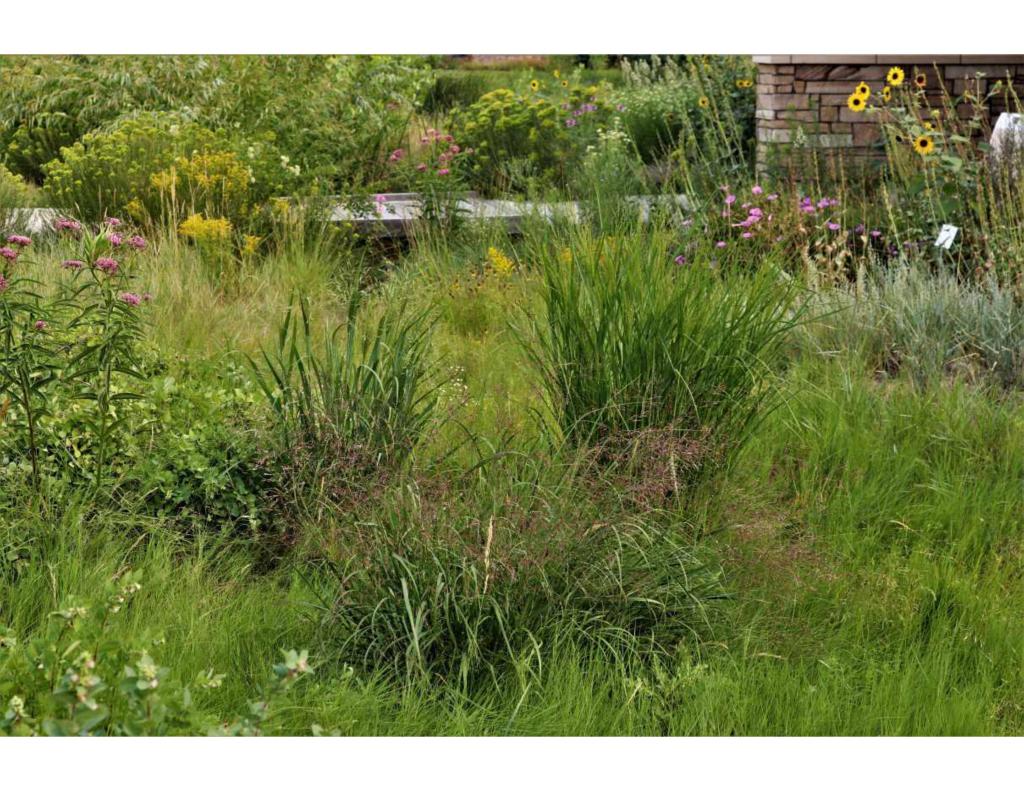

Well, using native plants doesn’t necessarily mean the landscape is wild or looks wild. You can use native plants and very formal arrangements, and there are good examples of that here in Centerra. There are these very straight bands of grasses that often use native species versus exotic introduced species. One example is where we have large bands of the little Bluestem grass. I would much rather see that kind of grass because it may go to seed and escape into nearby ponds. I would rather have that than the maiden grass that’s introduced from Asia invading our wetlands, so there is that aspect, too. If plants are going to jump the fence and get into open spaces, I would much rather see the native plants. But I think part of it also is the maintenance of these native landscapes and or habitat landscapes. There is a tendency to clean everything up in the fall, cut everything back make it look very manicured, and that means death for pollinators that might be attracted to that sort of landscape.

The reason is there are a lot of pollinators that might overwinter in the hollow stems of plants or overwinter in the base of the plants under leaves, and so another reason to leave the plants like that in the fall is that it protects the plants themselves from our frequent freeze-thaw cycles and it just creates an interesting textured landscape in the fall. I love to see the little snow caps that collect on top of flowers from the summer, and that’s something unique about the environment here in Colorado. All the plants just freeze-dry, and then in the fall versus on the East Coast or places that are wetter, the plants just turn into a kind of rotting mass in the fall and kind of get crushed by snow. Here they just seem to freeze dry in place, and it’s beautiful that really does sort of replicate something that happens in nature, so I mean, I think native plant landscapes could be anything from just a wild patch that really just kind of looks like a little section of the short grass prairie, or it could be a very intentionally arranged landscape using the vernacular of our western native plants.

Can a novice do native or sustainable landscape work?

Absolutely, yes. I think there are some principles involved, and that is, if we think about our landscape design as an ecological restoration, it means we’re looking at conditions that exist within the site. Even in the tiniest home yard, there are microclimates; they’re shady cool places, they’re sunny hot places, there are wetter places, drier places. If we think about the topography and the hydrology that exists even in tiny little yards and group plants together in communities, then we can replicate some of the functions in the environment. There are so many relationships between native plants and wildlife. We have over 900 species of native bees here in Colorado, and over 100 species of bees have shown up here in our gardens since we started to plant native plants, so it’s a matter of if you build it; they will come.

What should folks consider when attempting to do sustainable landscape design or management they want to convert their yard, get away from ornamentals, get away from Kentucky bluegrass?

Part of it is grouping plants together in communities with similar requirements. So if there are plants that need to have a little bit of moisture, those are grouped together in a zone. There are plants you can plant and water when you transplant them and never water them again, which could be grouped together in a zone. That is one of the seven principles of zero-scaping, which is creating these hydrological zones where plants are grouped together. I think that’s one of the central features of using native plants.

The other thing is, what if we say native plants? I always ask, “Native to what.” I meant to say if we say native to Colorado, that is an arbitrary political designation. Colorado is a state and has this kind of arbitrary boundary, but it doesn’t mean everything within that state is in the same climate zone or same ecological zone. In fact, in Colorado, we have more climate zones than a great many other states because we have the changes in elevation here. I think if we live along the Front Range, we should be thinking in terms of the prairie. The short grass prairie, or just the prairie in general, are ecosystems that we have a lot in common with, and that is thinking of everything from here to Montana to North Texas and East to Illinois. Those are all the Prairie states, so using plants that are adapted to the environment where we’re designing our garden.

There’s a man in Tucson, AZ, Brad Lancaster’s a landscape architect. The story that I’ve heard is that he cut a hole in the curb at his home and let the water flow into his landscape, which is kind of shaped like a bowl, so the water would flow in there and percolate into the ground. The city became aware that he had done this, and they came out they were going to write him a citation. He said OK, just wait a minute look at this beautiful park-like landscape here full of Palo Verde trees and native birds and so on. I never watered this landscape, and there must have been some conversations back at the city because now you can apply. The city will come out and knock a hole in your landscape, and the city is creating landscapes instead of a traffic island that’s raised up with landscaping. If the traffic island is like a bowl with landscaping and it just is a place where the rainwater goes.

It’s a little bit tricky in Colorado because the state was built on water law, and when a raindrop hits your roof, it belongs to somebody else. Only recently, the law has been changed so that for residential use, you can have a small rain barrel to water your landscape. Still, there is no law against channeling that water through your landscape, letting it percolate into the ground a little bit letting that water nourish the plants as it flows along and then off into some stormwater pond. For some reason, landscapers like to make everything flat, but if we have high areas and low areas again, then we can design our landscapes with this concept of putting things in the right hydrological zone.

So, we have wetland plants that are wetland plants in a landscape that is never watered; the blue vervain, it’s a wetland plant that we planted where our downspouts are, and all that water from the roof is concentrated there. So even the tiniest yard has that kind of different hydrological zones and thinking about where to put plants. In front of our building, we have a bioswale, so it takes all of the water that comes off of our parking lot, and it flows through a series of little pools. It’s not enough that we would have an abortive loss or anything. It’s like within 24 hours, all that water would disappear after a rain storm, but it just slows the water down a little bit and allows it to percolate into the ground, and people always comment about how beautiful the landscaping is in front of our building, and yet we never water that because in the high and dry areas, there are native plants that don’t like any water and in the bottom of it are things like the milkweeds and the tall grass species and golden rods that like a little bit more moisture and the plants seem to find the right zone for themselves and that’s a great example of how we can have these rain nourished gardens and like it’s called passive rainwater harvesting so just slowing down the water a little bit and letting that percolate the ground and nourish our landscapes.

So, for some folk ecology and economy, growth versus conservation are dichotomies, but it seems here at the High Plains Environmental Center that is not the case is that true.

That’s very true, and it’s interesting that you say ecology and economy because those two come from the same root word in Greek, Boyko’s, which is the household, and ecology, is the study of the household, and the economy is the management of the household, and I think there are those absolutely must work together. I think one of the mistakes of the environmental movement since the first Earth Day in 1970 is to be ecology versus economy or ecology versus business. Then you get people who are logging on the West Coast saying you care more about owls than you care about my family. I mean, all these things have to be considered and not create a kind of opposition. Still, we have this unique formula here where we’re benefiting the developer in this 3000-acre development. The development is also benefiting us. We’re also benefiting kids who live here because they get to grow up and see a bird and hear a frog, and we’re putting nature in people’s lives who live in this. Because we have beautiful nature, trails, birds, and so on, people want to live here, so it benefits the home builders. It also benefits the Environmental Center because the funding that is collected from the building permits is actually going to the restoration. Hence, it’s a really cool model where the business interests are funding the environmental interests, and the environmental interests are making a more marketable place to live. I think environmental and ecological or ecological and economic interests are also always impacting each other we just don’t always see the real cost of things, and people ask sometimes, you know should someone be able to have a 20,000 square foot home I think if they have the money, they could, but we need to charge the real cost for things like what it cost to dispose of waste and so on. If we’re paying the real costs and not just deferring those costs to future generations, to people who are in disenfranchised communities or other parts of the country where we’re taking their resources and they’re just becoming poorer, and we’re not really demonstrating the real cost and the source of our wealth is always from natural ways from the Earth so if we’re not managing that well we are in essence and in fact degrading our future economic prospects.

You’re listening to a public affair on KGNU. I’m Stacey Johnson; you’re visiting with Jim Tolstrup, executive director of the High Plains Environmental Center, discussing a range of contribution topics within the High Plains Environmental Center is available by visiting the website suburbitat.org.

On the website of the High Plains Environmental Center is a downloadable copy of a book called Suburbitat what’s mentioned in that book, and I’ll try to paraphrase this it says even with irrigation, the prolonged ugly duckling phase of native open space can be challenging for developers and HOA’s with many eyes and opinions surrounding the project.

What is your advice for overcoming those sorts of challenges?

Also, in a recent talk, you mentioned a quote by Rob Proctor, who said gardening is the world’s slowest performance art, and so for those who need immediate gratification or just stop with the finger beauty.

What’s your advice on overcoming those sorts of challenges?

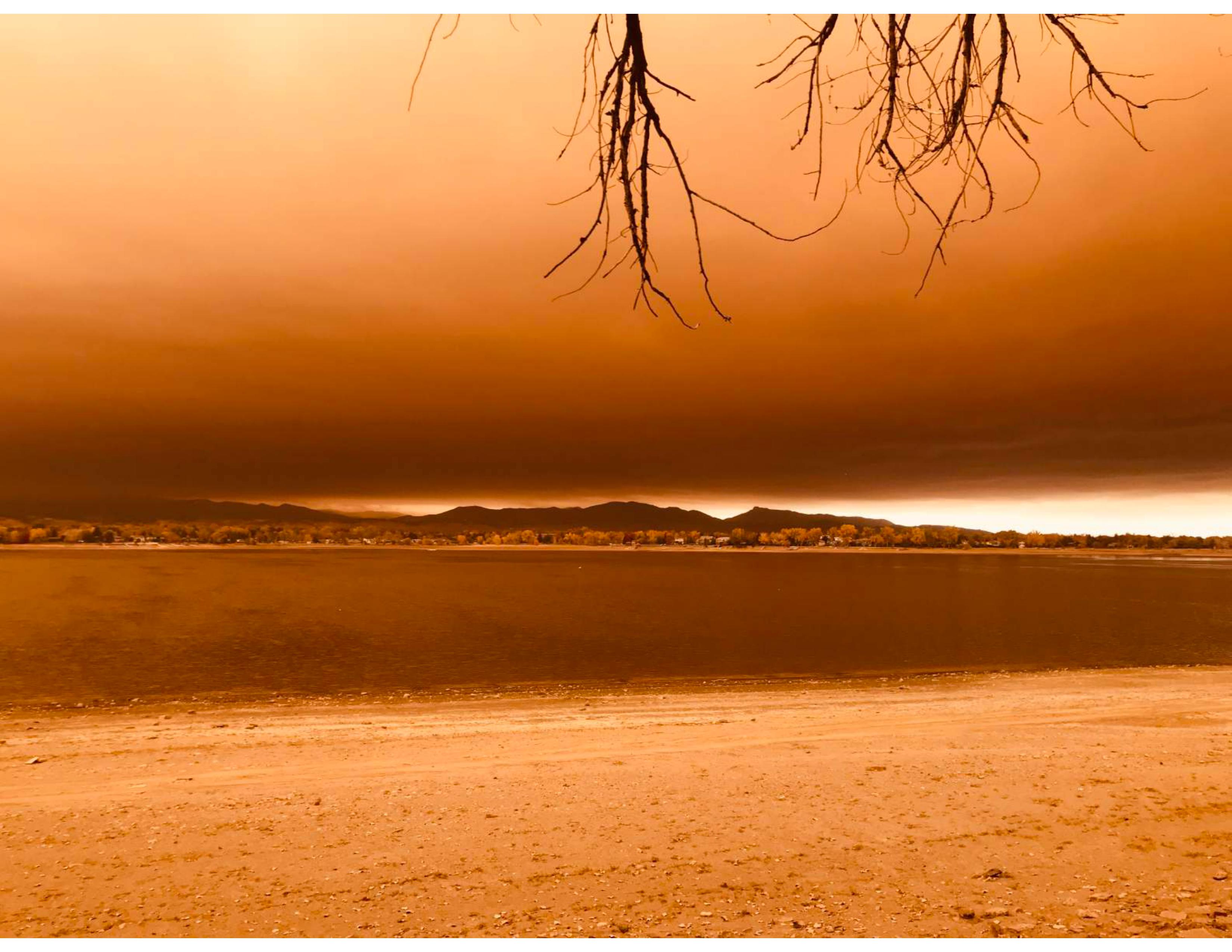

That’s absolutely true. That is a big challenge because people’s expectations and development timelines and restoration timelines are not the same, and this is not like a landscaper putting down Assad Man that they basically roll outside, and when they drive away, you have a lawn. This can take years even under good conditions, and I think it’s critical that people understand going in the realistic timelines for getting results. The benefits are that native grass costs a fraction to maintain of what it costs turf grass lawns and uses a fraction of the herbicide, pesticide, water, or any of those other things that are used so heavily on turf grass so it’s really worth it in the long run but there really is no way to move the dial ahead faster and if you have a situation where there is no water, and you’re just putting down native seed, and it could take a decade for that to establish. Particularly since the last two years, they say they aren’t the driest years in 1100 years in this region, so we’re just not going to see results without irrigation in that kind of situation, but the other part of this discussion is we don’t have the water. We do not have water, yet they keep doing this repeatedly, putting down these thirsty landscapes.

The average person in Colorado uses 150 gallons of water per day, and 60% of that goes to landscaping, so it’s 90 gallons of water per person per day to keep exotic landscapes on life support, and we do not have the resources for that so we’re going to have to come to terms with this and part of it is accepting we have to play by nature’s terms of what landscapes require, what is really sustainable here, and how long does it take to get things to establish.

One thing I’d like to do is take photographs of these areas because, as you mentioned you know Rob Proctor called gardening the world’s slowest performance art, and if you take pictures, you can see how things evolve over time you can see that something is happening it’s just happening at a, you know, different timeline than the way we usually see things getting built.

Does the work of the High Plains Environmental Center have any special significance for those that do not have a yard, have no access to the natural environment, or folks that are disabled indigenous people of color people from all walks of life?

There’s a lot in that question. I think one thing is that all of the programs we offer are free. We offer all of our educational programs at no cost; we offer raised garden beds to people in our community garden at no cost, and those could be people who live here in the likes of Centerra or nearby or anyone. So as a nonprofit, our mission is environmental education and environmental stewardship, and we are mandated by IRS to offer that to the public in general.

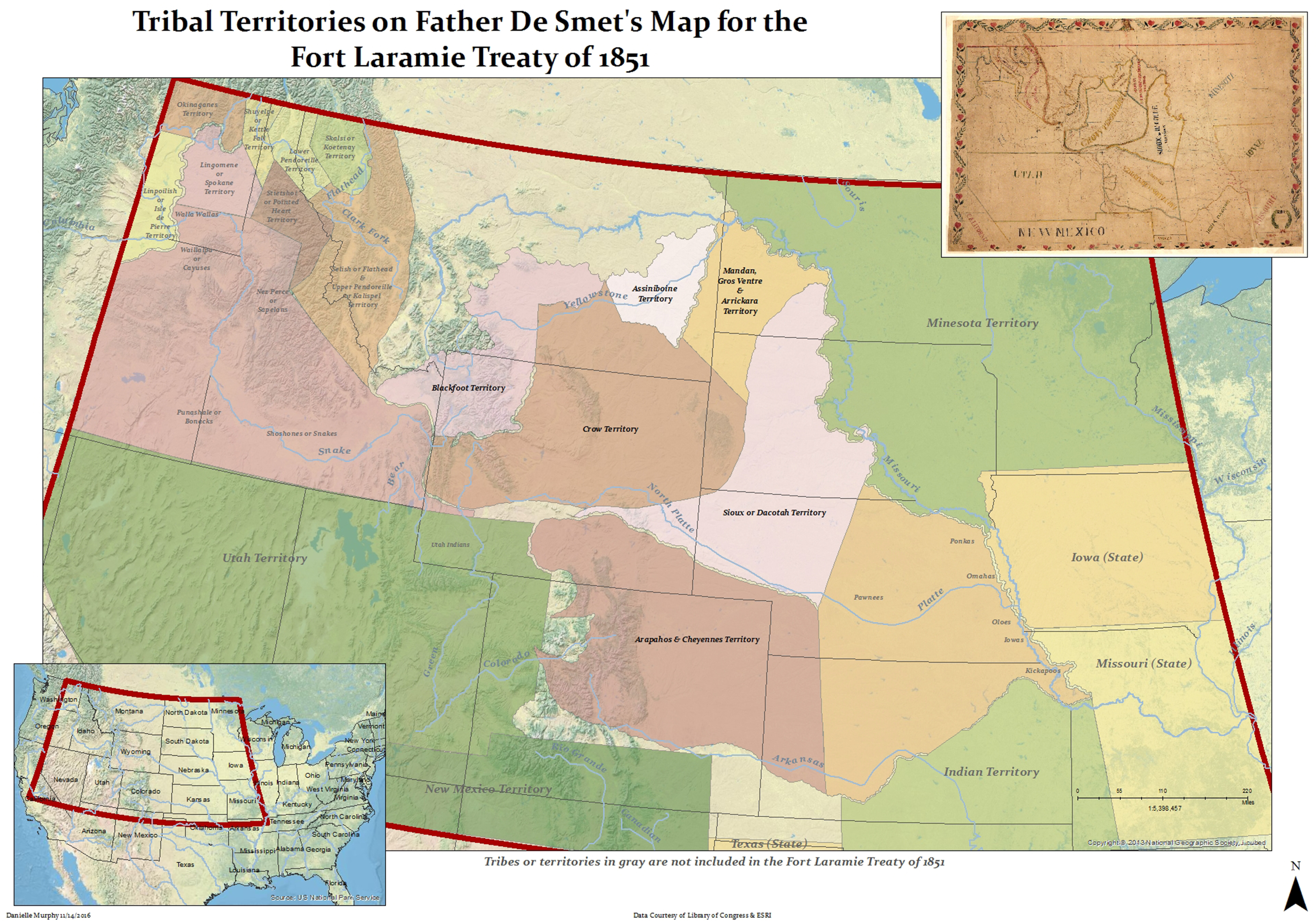

In terms of specifically the reconciliation with indigenous people, that is a big focus here at High Plains Environmental Center. We have both a garden that showcases plants used by tribes of the High Plains and frequently host events here that are culturally oriented events about the indigenous people who have existed in this region for over 12,000 years, so we are very interested in creating awareness of how Colorado didn’t just spring into existence in the 1850s, there’s been a culture here that has existed for over 12,000 years, and there are values connected with that culture that we need we need to understand a little bit more about our relationship to other things, that the world isn’t really just here for us to use, but we are part of the community, of the land. Aldo Leopold says when we see land as a community to which we belong, we will begin to use it with love and respect, and I think that’s an important aspect of understanding indigenous cultures. I also think that there is some reconciliation that needs to happen because we live on land that was taken through violent means and without the compensation that was promised through treaties and so on, and I don’t think that you can build a successful and sustainable future on that kind of foundation.

The Suburbitat book mentions that wetland environments comprise less than 2% of Colorado’s total land area and are utilized by 75% of all wildlife species at some point in their life cycle. Can you expand upon that and what the significance of that is for listeners.

Well, one of the earlier governors, and I can’t recall which one, wanted to arrange counties in Colorado along watersheds which really would have been a very smart way to do things because who is upstream and who is downstream are dependent on one another and we have significantly altered the hydrology in this area. They used to have this thing called the June Rise when all the snow melted that would just tear trees out. the South Platte River that didn’t have the trees on it that it had now. Or the North Platte, the South Platte, these rivers didn’t have the trees they have now because they were just come tearing down from the mountains and rip all that stuff out. They actually have to create sandbars now in Carney, Nebraska, for the Sandhill cranes because the scrubbing action of that sort of flood doesn’t exist anymore, so they have to replicate it.

One of the interesting things that we can do is whenever developers build impermeable surfaces, rooftops, parking lots, and roads, the government requires that flood mitigation be put in place so that all that water doesn’t go someplace where we don’t want it to go. So, stormwater ponds and stormwater conveyances are created. The previous version of this in the 1950s and 60s is that water just went in the storm drain, and it was piped raw into a lake or river and dumped with all that sediment and runoff into the river. Now there’s more of an idea of creating water quality ponds that allow the sediment to drop out of the runoff, and if those ponds contain native vegetation, it can help to sequester some of the nutrient runoff that comes from various activities in the way that we live, fertilizing and so on. Using that nutrient runoff can prevent algae in our ponds and lakes. The algae reduce the oxygen in the water and can kill off fish and other aquatic life. These urban stormwater ponds are a tremendous opportunity for restoring habitat for wetland plants, amphibians, birds, and all kinds of things. I think this is one of our best opportunities for restoring nature in the built environment as we look at building stormwater ponds and conveyances.

If you are just tuning in, this is a public affair on KGNU. I’m Stacey Johnson. This evening we are visiting with Jim Tolstrup, executive director of the High Plains Environmental Center, discussing a range of conservation topics within an urban environment.

Some other statements stood out to me in your book. One is the short grass prairie, the area most impacted by agriculture and land development and is considered the most degraded ecosystem in North America. Another quote it’s important to note that merely planting native grass does not make a Prairie a real Prairie is like an old-growth forest that requires centuries, if not millennia, to establish. Once destroyed, it does not reestablish quickly, and so those statements seem daunting for folks considering native landscapes or HOAs and such can the High Plains Environmental Center is a place of hope amongst those sorts of daunting realities.

If you fly into DIA and you look down, you can see how dramatically altered that landscape is; you see all those crop circles with irrigation. They say that the High Plains, the region that we live in, which extends from North Texas up to southern Montana, is one of the most degraded ecosystems in the United States. Less than 3% of the high plains are still intact. So that means all the animals that live there, the Black Tailed Prairie Dogs, the Black Footed Ferrets, and so on, disappear because that environment is gone.

Yes, a Prairie is like an old forest; there’s a lot more going on there than just grass; almost all of the biodiversity of the Prairie is below ground, and there are all kinds of soil microbiota and things happening there. That doesn’t automatically replicate, and it isn’t like EO Wilson called the New England Forest the ecological wonder of the 20th century; at the beginning of the 20th century, Massachusetts was 90% agriculture; at the end of the 20th century, it was 70% forest, and that forest replicated itself but that’s a region that gets about an inch of rain a week, and here we get 12 to 14 inches of precipitation in a year and some years we don’t get that so there’s no grass Prairie isn’t just going to restore itself.

There has been in a lot of places along the Front Range this buy and dry strategy where municipalities would buy farms, strip off the water rights and just abandon the land, and the land just turns into kosha weeds, and it’s not just going turn back into short grass prairie. Laws are changing, so that isn’t possible anymore. If that land is going to be stripped of water rights and abandoned, it has to be restored with native grass, and as we’ve said earlier, that is a long process but an interesting example of how the short grass prairie could be restored, lies in the story of the black-footed ferret reintroduction. This is the most endangered mammal in North America and was thought to be extinct until a few animals, I think maybe a total of 16, were found around Matisi, Wyoming, and from that, through a federal program, the ferrets have been bred. There’s a facility in Car Colorado just north of Fort Collins where these animals are born and introduced into the wild. Though lots of ranchers are resistant to the idea of releasing a federally protected animal onto their land, and also the Prairie dogs require large expanses of Prairie dog colonies, something that ranchers also don’t like but a monetary compensation was put in place to pay the ranchers for the areas that are kept in Prairie dogs and the Safe Harbor Agreement was put in place so that if somebody runs over black-footed ferret with their pickup or something like that, unless they intentionally harm the animal, there is no penalty. So again, the Safe Harbor Agreement protects them from any liability, and I think in that there’s a great example of how we can restart the short grass Prairie and it goes back to your prior question about ecology versus economy. There needs to be some kind of monetary compensation if somebody is putting in the time and expense and limiting their own use of their property in restoring the environment. In the built environment and designed communities, many developers are attempting to use the native grasses because they understand that, in the long run, it costs a lot less to manage, and it doesn’t use lots of water that they may not actually have available. I think developers get it in terms of the economics of the situation, and again, you know, it’s how to get these ecological restoration values to work together with economic values. When you can get those to work together, that is our recipe for success.

How should listeners think about weeds within the concepts of restoration, sustainable landscaping, or native plants as a person who has been a gardener and knows the land

As a person who has been a gardener, we have many more challenges in this region than what is typical, partly on the large scale, if you’re a developer and you’re trying to establish native habitats and native plants. What other properties around you are doing is really critical. That’s why we have things called the weed cooperative. If you manage weeds and the adjacent landowners don’t manage weeds, there’s going to be a kind of blowback, like quite literally on your property, and that’s an important consideration in terms of strategies of how to manage weeds.

One thing I have to say is we are not averse to the use of herbicides, and people will ask, “you’re a Nature Center; why do you use herbicides?” I would say since Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, a lot of chemicals have evolved that are very specific targets. They don’t even kill all plants. They’ll kill certain plants; there are some like that Canada Thistle that can really only be controlled effectively with some very selective herbicides and one thing is in restoring natural areas, we use a fraction, a tiny fraction of the amount of chemical that is used on your typical school ball field, on people’s front lawns and we use it on very specific targets so here at HPEC. I employ people who have master’s degrees in Agronomy, who have degrees in range management, and so on, and these people know the difference between plants. They can identify plants in the field and use a particular chemical on a specific plant. So, it could be like, you know, ounces per acre of chemicals that are being used a fraction of what’s being used on turf grass and used on very specific targets. Our goal is to have fewer invasive plants and more native plants, and it isn’t something that is going to fix itself without human intervention. Some of these plants are like Pandora’s box, really, once it’s out in the environment. There are weeds that have been introduced from Europe and Asia that are really never going to be completely gone from this region, and if we want to have a healthy ecosystem, we are going to have to manage those on our property because the invasives just outcompete the native plants and don’t provide the same benefits to pollinators and wildlife that evolved with the native plants.

One of the things I think is who gets their first wins, so if you see native grasses but lots of invasive plants come up, they can outcompete the native grass. But once you have a healthy stand of grass and native plants, it’s very difficult for weeds to get established in a healthy plant community. It’s also essential to manage that so people are planting native grasses, but they’re treating it like a lawn, and you’re scalping the native grass. I’ve seen a lot of disasters with Buffalo grass which is great turf grass, but people scalp it, and then they like water it like it’s Kentucky bluegrass, and you’re just going to have a weedy unhappy stand for grass. Because we haven’t seen a lot of good examples, I think that that’s why more people aren’t doing it.

Is there anything you would like to mention that hasn’t been covered?

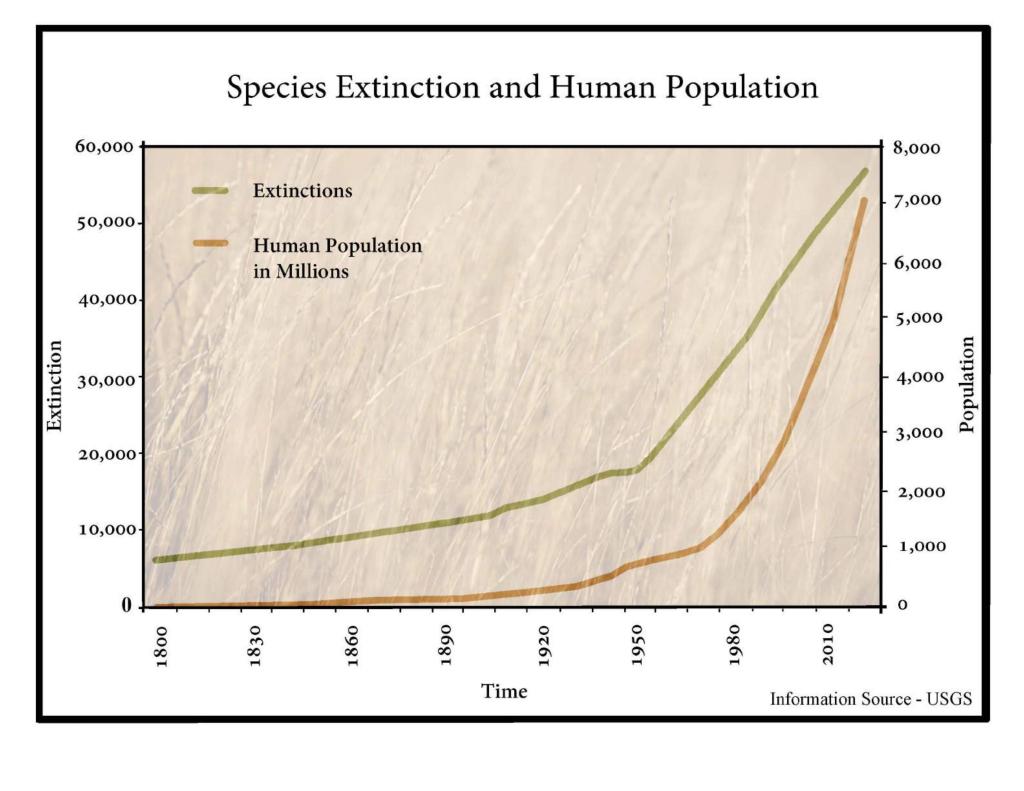

We are now in a situation where our landscapes must be more than just pretty. The human population on Earth has doubled; we are now over 7 billion people. I heard the statistic from David Attenborough that 96% of the weight of mammals on Earth as human beings, their livestock, and pets, and the other 4% are what we call wildlife. That is a very daunting statistic. There was a time when human beings struggled to claw their survival out of the wilderness and nature. It is completely turned around to the point that, as Doug Thalami says, 98% of the lower 48 states have been altered for human use, and we are outpacing nature dramatically on Earth. This is more than just saving nature because it’s pretty or saving nature because you know birds are nice or because we like to see animals. We cannot survive without biodiversity on Earth. We cannot survive on a planet that is occupied only by human beings and their livestock and pets, so it is our own qualified self-interest that we have to work to save biodiversity.

All extinctions happen at home, we don’t have elephants and lions wandering around our gardens, but if you are a farmer in Africa, you might want to see elephants disappear because they’re stomping through your fields. We need to think in terms of how we can preserve the biodiversity where we live. Audubon did a study in 2019 that said that 60% of birds in North America are threatened with extinction due to climate change, and that is just a catastrophic number. I mean, we talk about how we are in an age of mega extinction; you know, a huge period of extinction. We have to do everything we can to prevent that from happening, not only because we have no right to destroy life on Earth but also because we will be destroying ourselves. But turning our lawn into a native landscape is the low-hanging fruit; this should have been done yesterday. It’s something that’s very easy to do, it’s beautiful, and it’s appropriate to the climate where we live.

Jim Tolstrup, I appreciate your time today and sharing your wisdom with listeners of KGNU. Thank you very much.