By: Jim Tolstrup

Responding to the Climate Crisis in Colorado Landscapes

Links:

- Montane zone: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Montane_ecosystems

- Sub-alpine forest: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/agricultural-and-biological-sciences/subalpine-forest

- mountain pine beetle: https://apps.fs.usda.gov/r6_decaid/views/mountain_pine_beetle.html

- ips beetle: https://csfs.colostate.edu/forest-management/common-forest-insects-diseases/ips-beetle/

- Marshall fire: https://www.denverpost.com/2022/01/15/marshall-fire-insurance-losses-housing-density/

- Suburbitat: https://www.amazon.com/SUBURBITAT-guide-restoring-nature-where-ebook/dp/B096DGP8B3/ref=zg_bsnr_157566011_2/147-4279448-9133168?_encoding=UTF8&psc=1&refRID=1PMWMX2M2943RHX6S7XX

- High Plains Environmental Center: https://suburbitat.org/

Last year I wrote a book about restoring nature in the environments where we live, work, and play focusing on the use of native plants in landscaping and habitat restoration. At the end of the book, I included the following comment: The communities that we design and build need to have a positive effect on natural areas and resources, or nature will have a negative effect on us.

The previous summer hundreds of thousands of acres of forests were burning throughout the West. In cities along Colorado’s Front Range, fumes and smoke hung in the air so thickly at times that it created an otherworldly light. Air quality was in the poor to dangerous range off and on from August through much of October.

My comment was meant to be philosophical. Of course, there are feedback loops from nature, and a species that destroys its environment will begin to die out as its ecosystem declines. But humans are good at manipulating that feedback, or so we may believe. The thought that a raging fire could consume an entire neighborhood, destroying nearly 1,000 homes in a single afternoon, as it did in Superior, Colorado on Dec. 30, 2021, was beyond anything we had previously imagined. This single event shattered the notion of a “fire season” in Colorado and introduced us to the term and the lived experience of an “urban fire storm.”

The fire cycle is certainly not new to our region. Historically, lightning strikes caused low-level grass fires from the prairie to the montane zone, elevations of approximately 4,500 to 9,000 feet. The montane zone sometimes called the “ponderosa pine savanna,” is a landscape shaped by fire. Ponderosa pines naturally lose their lower branches, which otherwise could become ladder fuel that could help a fire reach the crown of the tree. The pumpkin orange bark of a mature ponderosa pine has evolved to slough off in layers when exposed to fire, making them somewhat flame resistant.

Before the arrival of white settlers, fire shaped the montane zone into a park-like environment with large trees spaced far apart in a grassland filled with shrubs and wildflowers. Fire helped to clear out and renew the understory periodically, and kept these trees from becoming too crowded. The wide spacing of trees helped to keep this old-growth forest healthy by limiting the number of trees, thereby reducing competition for available ground moisture.

Low-intensity fires can help to regenerate growth in Western landscapes.

Snowmelt from Colorado’s subalpine forests provides water to over 40 million people in seven Western states.

Indigenous people used fire to regenerate the land and improve habitat for the game on which they depended. The absence of these traditional land management practices, combined with the excessive suppression of naturally occurring fires within the last century, has resulted in an overgrown, and less resilient forest. It’s estimated that 80% of the trees in Colorado are less than 100 years old. People who say that “trees are the answer” and apply this standard universally, regardless of bioregion, may be missing an important point about how our ecosystem functions in the Rocky Mountain West.

When fires ignite in the overgrown forests that currently exist, they don’t just burn along the forest floor. They leap up into the crowns of trees, creating such an intensity of heat that they often burn the soil, which undermines the forest’s recovery. When storm events hit the scorched slopes following this type of fire it can cause erosion, siltation of streams and acidification of water which corrodes the pipes of municipal water supplies.

In both the montane and sup-alpine forest prolonged drought and milder winters have exacerbated the issues brought on by overcrowding leading to an outbreak of mountain pine beetle, ips beetle and other insects that have killed large numbers of trees over vast areas. In some ways it could be said that these insects are doing the work of forest thinning in the absence of fire. In many parts of the montane forest the beetle kill resembles a burn pattern, taking out a group of trees here and leaving others there.

However, there are many places where the subalpine forest has been reduced to nothing but a stand of dead trees, as far as the eye can see. But on closer examination, there is a tiny understory of forest already reestablishing in many areas. In 100 years these large areas of dead forest may be completely regenerated. But there is some concern that rising temperatures and a continual drying trend may not allow the subalpine forest to recover.

Water supplies in much of the West are dependent on Colorado’s high-altitude forests that trap and store snowfall. As snow in the cool sub-alpine forest begins to melt, it replenishes streams and rivers, including the Colorado River, which supplies water to 40 million people in seven western states.

The growth of cities in the American West has increased water consumption from the Colorado River and pushed this critical natural resource beyond its recharge capacity. It is possible that we could reduce some of this demand within the communities that we design and build by switching to a style of landscaping that is more appropriate for our region, thereby conserving water while restoring some of our state’s unique biodiversity.

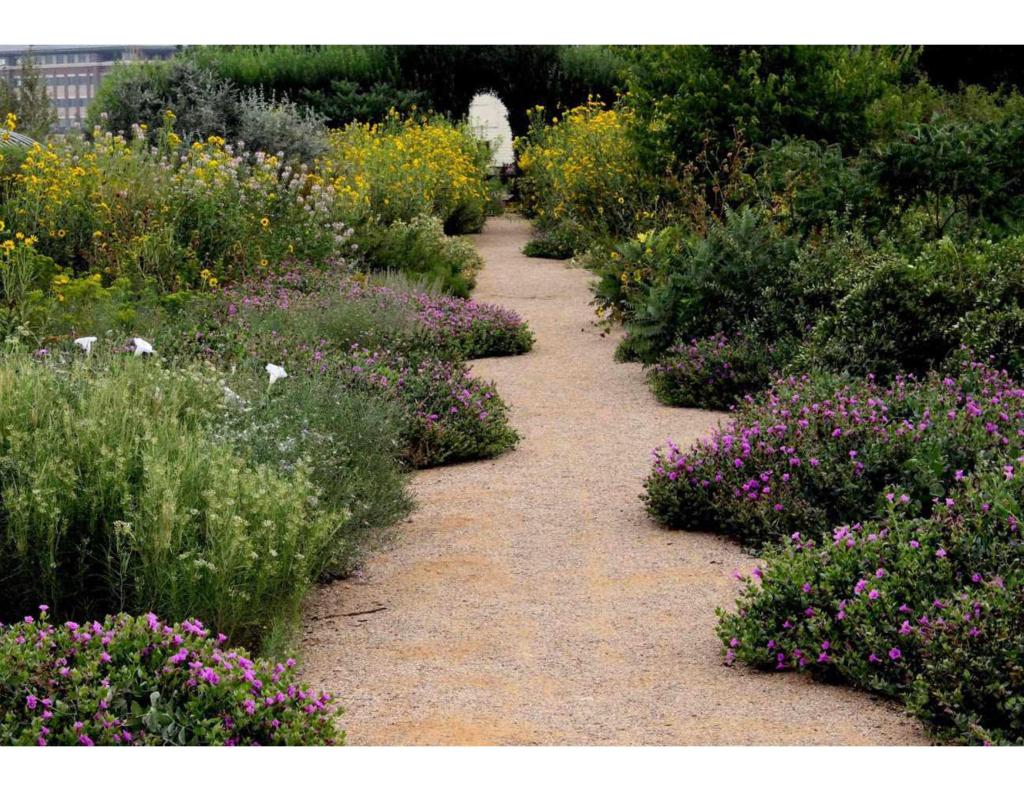

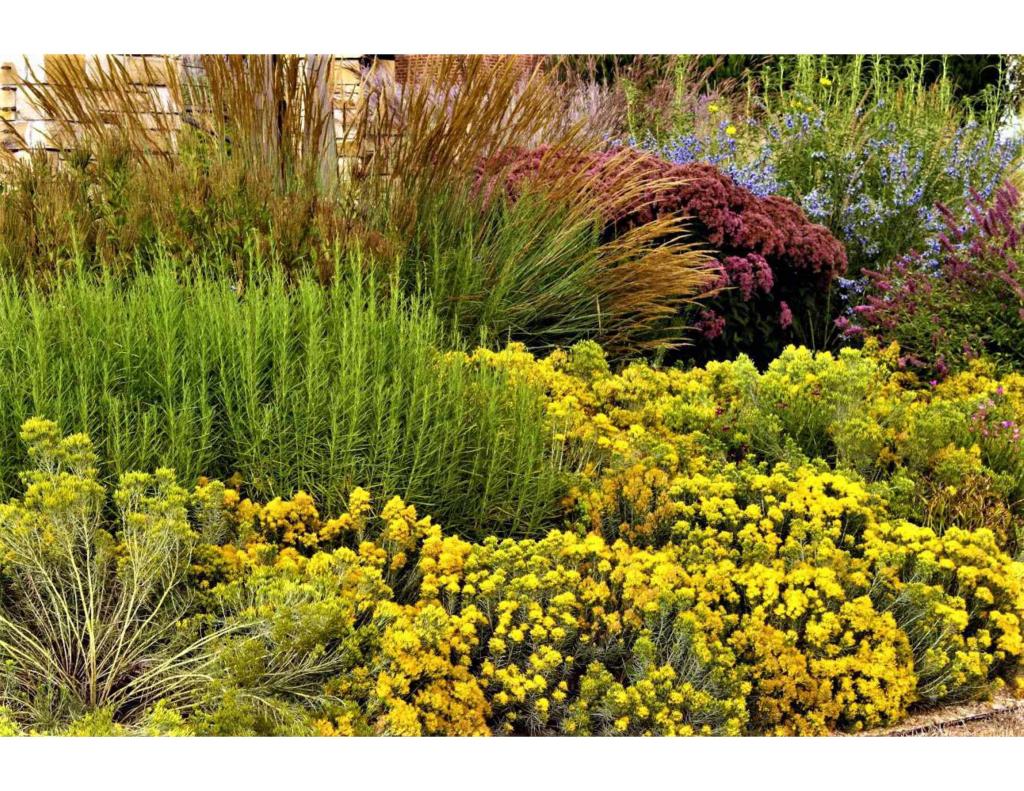

Western native plants are adapted to the Colorado region’s bright sun, high altitude, and windy and dry conditions.

Here in the cities on Colorado’s Front Range, a region that typically gets 12–14 inches of precipitation per year, the average person uses 150 gallons of water per day. About 60 percent of residential water consumption goes to support landscaping. This amounts to approximately 90 gallons of water per person per day used to keep exotic landscapes on life support.

Colorado’s population in 1900 was 543,000. By 2019, the population had increased over tenfold to 5.7 million. Over the next 20 years, Colorado’s population is expected to grow by roughly 30%, increasing from 5.7 million in 2019 to 7.52 million in 2040.

Global climate change is already impacting the timing and the amount of water available in the state. Rising temperatures can lead to fewer, but more-intense precipitation events and can alter the ways in which plants grow. The transpiration process of plants pulls water from the soil and disperses it into the atmosphere. Transpiration increases as temperatures warm, which causes the plants to use more water and further dries out the soil.

Although our growing population and a changing climate will reduce available water, thus far, we have made virtually no effort to conserve water in landscaping. However, the rising cost of water is beginning to change how municipalities, developers and landscape designers are re-envisioning “regionally appropriate landscapes” that utilize native plants adapted to our high altitude, bright sun and dry climate.

Native landscapes can help wildlife survive during periods of drought. In the summer of 2020, during a prolonged drought, our gardens in Loveland, Colorado were thronging with birds and pollinators. Hummingbirds, which are usually found at higher elevations in summer, buzzed through our gardens in record numbers. Songbirds flocked to our gardens as well, seeking fruit, seeds and insects when many other sites were barren and dry. Hiking in the mountains to find wildflower seeds yielded nothing because many plants had flowered little, or not at all.

By late summer the dead standing timber in the high country, fanned by a hot dry wind, exploded into flames that burned over 665,000 acres. The resulting fires killed countless thousands of wild animals and caused $266 million in damages. 2020 was the costliest fire season in Colorado history until the following year when the Marshall fire broke this record in a single afternoon.

After the long summer’s drought of 2020, stress that resulted from fires and heavy smoke, and a sudden deep freeze in early September sent millions of birds in the Rocky Mountain West into a migration for which they were not prepared. Tens of thousands, perhaps hundreds of thousands, of birds were found dead in Southwestern states, where birds literally dropped from the sky.

With the growing threat of extinction facing so many species, today’s gardens need to be more than just pretty; they need to serve an ecological function. Thankfully, birds like the cedar waxwing are also protected under the U.S. Migratory Bird Treaty Act.

Holding one tiny bird while thousands of others flocked to our gardens under a smoke-filled sky.

A subsequent necropsy confirmed that the birds had died of starvation, unable to gain sufficient weight before migrating. As the effects of climate change increase occurrences such as this, it increases the need for us to subsidize the diet of our wild birds. A study undertaken by the Audubon Society says that 389 species, roughly two-thirds of all the birds in the U.S. are threatened with extinction or significant loss of habitable range due to climate change. Providing habitat within the landscapes that we design could make an enormous difference to their survival.

Full disclosure – shifting landscape practices, although perhaps the low hanging fruit, is not in itself enough to solve our water supply problems. It’s important to note that an estimated 50% of water used in the Colorado River Basin goes to raising cattle, and as much as 25% of our water nation-wide. While it could be argued that meat is the only sustainable food in our region because grazing animals do not destroy the native plant community in the same way that cultivation does, this does not represent the facts of the situation. Cattle are not drinking all this water. The water is used to grow crops to fatten cattle in crowded feed lots.

Solving the problems presented by climate change is, of course, not a simple matter. It will require two things that seem to be in extremely short supply, a widespread acceptance of demonstrable facts, based on scientific research, and a willingness to work with a broad base of stakeholders and partners including businesses, farmers, citizens, political leaders, and nature herself.

Many native plants have interdependent relationships with the insects that co-evolved with them, such as this two-tailed swallowtail (Papilio multicaudata)

The simple notion that it’s more beneficial and cost-effective to utilize native plants vs. laying down thousands of acres of irrigated turf would seem to be a foregone conclusion, but the notion is only slowly taking hold. Nonetheless, this conversion, if only out of the necessity of water shortages, is inevitable. But this is not an argument for austerity. This is rather an invitation to celebrate landscapes that are vibrant and interesting year-round, in a way that allows other beings, present and future, to do the same.

We have observed firsthand how dramatically and rapidly our local birds and pollinators recover when we grow native plants in our gardens. Celebrating our native biodiversity can restore our relationship to the land and may allow the new civilization that we have built on this land to continue, in harmony with nature.

Jim Tolstrup, author of “SUBURBITAT,” is the executive director of the High Plains Environmental Center, in Loveland, Colorado, a unique model for restoring nature where we live, work, and play.